Teacher recruitment and retention have been a big topic of discussion for a long time, and the conversation has only grown in volume these last several years. In three rounds of North Dakota United member polling conducted in the last two years, 35% of educators said that they were considering leaving the profession. The top reasons cited were burnout/additional stress (82%), current salaries (61%), and extra duties becoming burdensome (60%).

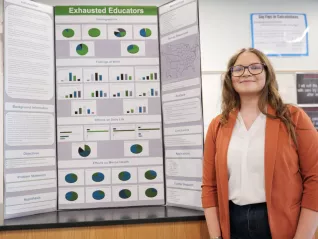

Certainly, the public is talking about this issue and coming around to the realization that it is a growing problem for communities of all sizes. In one of North Dakota’s smaller communities, Flasher, one sophomore, Sophia Jochim, dedicated a year’s efforts into studying this epidemic as a science fair project. She first turned to her science teacher, Tana Schafer, for guidance on where to start and how. Schafer recommended she talk to a few names, including North Dakota United President Nick Archuleta. We sat down with Sophia, Tana and Nick in the high school science classroom at Flasher Public School this past May, during Teacher Appreciation Week, to talk about the experiences they shared.

Did you grow up in Flasher?

Sophia Jochim: My dad grew up in Flasher, since he was little, and my mom grew up in Mott. And they got married in Flasher and then had six kids. But yeah, I’ve been here since kindergarten.

Your interest in science, when did that start? And were there people in your life who really inspired your love for science?

SJ: I always liked science fair because we start in fifth grade and I think I really liked it because I got to talk to people and because I like to talk. I’m just a big people person. As long as you find something that you’re passionate about, you can turn almost anything into a science fair project. And that’s what I’ve done here. This is actually a continuation from my project last year. Last year, I did mental health and 911 dispatchers. And then next year I plan to continue this and do a survey on bankers or something, and then compare and contrast with those jobs.

How did you decide to turn the focus of this year’s project to teachers?

We start kind of earlier in the year. We pick our topics, and then we find a question. I had brought it up to Mrs. Schafer, and she said, “Let’s do something with the teachers.”

How long have you been teaching science at Flasher? And did you also grow up here?

Tana Schafer: I have worked in the school since 2013. I’ve been a science teacher for the last six years. And my husband is from the Flasher area. I’m not originally from here, but we moved to Flasher.

Since you started as a science teacher and working with students on science fairs, how much work goes into it and how receptive are kids today in these projects?

TS: This is my fifth year doing science fair and the fourth year we’ve been able to present them because of the COVID year.

When I first started, it was a fight. Families didn’t want me to do it. Kids didn’t want to do it. It was this really big deal. And it’s just grown into a thing. Like, it’s science fair in Flasher. It’s a thing. And kids want to do it because they know that we’re really successful with it. Kids get excited about it, and it becomes something they look forward to every year.

Walking through the hallways, I saw signs on the locker room, wishing students luck at the state science fair. What does that mean to you?

SJ: It helps a lot because, I mean, Flasher is very high on the sports side. A lot of the smarter kids or academic kids don’t always get a lot of the attention. I mean, truly, we’re the kids that go the farthest. I don’t know how many kids we sent to state this year.

TS: Thirty. We can send 48 from our region. Our region had about 180 kids this year, and 30 of the 48 came from Flasher this year, actually.

When you started working on the project did you discuss the idea with Mrs. Schafer and was she the person who encouraged you to reach out to Nick?

SJ: Yeah. She wrote down a couple emails. I think I started at Kirsten (Baesler), then she sent me to Nick.

Nick Archuleta: And of course, Kirsten is from Flasher.

TS: She’s a huge proponent for science fair, too. So, I knew that she would be a great one for Sophia to reach out to. I was like, start with her. She’ll point you in the right direction.

In talking with Nick, what things did you learn?

SJ: I met with Nick twice over Zoom. I knew he was a big name in the education system, so I knew I could bring him up a lot in my conversations with the judges. And you had told me that there was a school that has higher paid teachers and teachers just get to teach there. And I think that’s what I got to use a lot from him in my conversation that teachers just got to teach.

NA: I think I talked about Finland. In Finland, every teacher there has a master’s degree. There is real competition to get into the colleges of education there. … Most of that education is paid for by the government. And here’s why: Finland knows exactly what the United States also knows, and that is, if you’re going to have a successful country, you have to have an educated population. So, they invest in their education, and they invest in their children’s education. Because, frankly, we don’t do anything more important as a society than invest in our future. And that means educating our future. And so Finland gets it, and Finland does it. The United States also gets it, but we don’t invest in the same way. We don’t make it as high a priority as we should. But most importantly, if you talk about teachers and the profession of education in Finland, they are held in the same esteem as their lawyers and their doctors and their engineers and accountants. That’s doesn’t happen in the United States. So, what we need to do is find a way to return the profession to its previous luster. We need to investigate what is driving people out of the profession. And that’s why I think your work here is really important because it does shine a light on something that teachers are experiencing every day.

Can you share a little of what you told the judges when they were evaluating your project?

SJ: My objectives were to gain an understanding of teachers’ duties and responsibilities, understand the pressures faced, and uncover problems associated with decreased mental health in the workplace. My problem, obviously, was: What effect does current teaching have on mental health? And I thought the more experienced the teacher, the (better their) mental health. From there, I shadowed teachers at my school. I observed mental health, co-worker interactions and demeanor during work. Using Google Forms, I created a 52-question survey. I split between demographics, feelings at work, effects on daily life and effects on mental health. I consulted and reviewed my survey with (Nick Archuleta) and distributed my survey nationwide, in all 50 states, 36 outside of the United States, and I received over 1,200 responses. For demographics. I asked basic questions: gender, age, their job title, marital status, total years of teaching (experience), degree and level that they’re teaching, and if they had any children of their own. The next session was feelings at work. I asked, on a scale of 1 to 10, how comfortable are you in meetings? How comfortable are you with your additional work, training, lack of ability and control, satisfaction? And then my effects on daily life was: How much time are they spending on professional development, academic documentation, parent communication and classroom management? And then I asked, has their school ever experienced a traumatic event? And then the last section was effects on mental health. Are you tired of your students? Are you weary with all your job responsibilities? Does your job still excite you? And then, for my analysis, teachers experiencing burnout at the beginning of this school year had notably worse classroom management by spring than other teachers. 49.9% of respondents stated they have experienced a traumatic event at work. 33.1% showed lower time pressure. 32.4% of teachers struggle with increased anxiety that is work-related. And 54.1% feel constant frustration at work. And then, in conclusion, careers in teaching are still extremely rewarding. Teachers gain confidence through experience. Administrative-to-employee relationships may be tense, and careers in teaching may negatively affect emotional and mental health.

What would you say is the most surprising thing that you discovered during this project?

SJ: Probably the amount of time spent on classroom management. I think that’s increased (in) the past probably three years since COVID. When we all got sent home to when we all came back, I think, students kind of shifted a lot. I mean, just noticing it between my classmates, too, to where we don’t want to listen, we don’t want to work. The teachers have to deal with it, and then the teachers, send the students out … to the principal, and the principal sends them right back in maybe five minutes later with little to no punishment, when punishment is usually needed.

TS: Reading some of the results, a lot of teachers mentioned that their administrators do not do anything for behaviors anymore. So much of it is just on the teachers. There is no support. So, if they can’t take care of it in their classroom, it just boils over. And that’s what’s burning a lot of teachers out.

NA: I have an opportunity to talk to teachers across the state. And there was a woman who was a librarian at a middle school, and she was just beside herself after coming back from COVID. They were gone that entire spring, and then they were hybrid after that. And she said the basic things, like teaching kids that they can’t just fall asleep in class or they can’t put their feet on the desk. Things that are normal, that you cover in first grade or kindergarten, she had to reteach all that. And that just tore her up, she was ready to quit.

Do you think that your fellow students, Sophia, and your colleagues in education, Tana, or the general public really have a good idea of the amount of stress that teachers are facing now?

SJ: No. I think it can be a little bit lucky (in Flasher) because we’re smaller, to where once we get older, we kind of bond together with the teachers to where we kind of understand like, okay, she’s having a bad day. We’d better sit down and be good. And I don’t think our community understands. I think really the only way to understand it is if you are a teacher or you’re married to a teacher or related to a teacher. I think, any other way, you just don’t understand it.

TS: Yeah, I agree with what she said, too. We have our kids for six years in high school. And as we are with them, you get to know them. And, I mean, we’re really a family here. I would really refer to our school as a family. And I can tell the kids, I can look at them and go, “Okay, guys, having a tough day.” And their attitudes will just change. But like you said, looking at the colleagues and things like that, I know it was interesting because once this survey was done and I was talking to different teachers, I told them, we’re not alone. I think that that was really inspiring to hear. I think our community is pretty supportive of our teachers. But if things don’t change, we’re going to lose them. I mean, you talk to other staff members and they’re just done. We’re fried, we’re tired. It’s one more thing. It’s one more thing. It’s one more thing. Now we have to do this coding, the computer science thing came out great. It’s phenomenal. But you added one more thing, and you’re never taking anything away. So, it’s how do you push more and more and more in? It’s getting to be a lot. And I see it, that we’re starting to lose teachers.

NA: On one of our surveys, teachers in the 30- to 39-year age group, we asked when they first started teaching, did you see yourself retiring after a long career in education? 91% of them said yes. Last year, that number was down to 46%. And then, when you consider all these communities in North Dakota that are hiring teachers from the Philippines and from other places. That’s no slam against those teachers. I mean, they’re good at what they do, and by and large, I think they’re as successful as any other teachers. But it just seems to be sort of a blind spot in the public where we’re not doing enough to encourage our own folks here to go into teaching.

TS: A lot of it is, I feel, the financial aspect of it, too. I don’t know a single teacher here who doesn’t have some type of side hustle. There’s something on the side, because you have to in order to financially make ends meet. … I would say, I love my job. I love to teach these kids. But if I didn’t have something on the side that financially kept my family stable, I couldn’t stay here. I think that’s driving a lot of people out, too.

When a teacher leaves a smaller school in a rural community, how difficult is it to recruit a new teacher into the community and to retain them long-term?

TS: My job was actually a revolving door. I’m a business major, by trade. I did not go to school for education. I was here as a para, and it was just a new science teacher every year. The kids weren’t learning anything. … I had a passion for science fair when I was a kid, and I’m like, this is not okay with me. And so, I just kind of stepped into the role. And you have to find people in your small communities to do that. … We’re a stepping stone. We are a place for a first-year teacher to get the experience (in order) to get a job somewhere else. And so, in our community, we have to grow our own. We have to grow our kids to become teachers, to want to move home and teach, because otherwise we don’t fill those positions with people who are of substance or who are going to be a career teacher. We just don’t get career teachers unless you’re rooted in this community.

NA: I think that’s a really big point. We’ve been pushing for that in the Legislature. What are we doing to incentivize young people? We need science teachers in Flasher or a business teacher someplace else. Why aren’t we growing them? I was talking to a senator … he said, “So, Nick, what is the problem with teacher salaries?” And I said, “Well, they’re too low.” And he said, “Yeah, but here’s the thing, if I have a shortage of workers and I’ve got jobs that need to get done, I pay everybody more.” And I said, “Yes, yes, you’re getting it. But that’s not what happens in public education, you know?” And he said, “Well, it should.” I said, “Maybe you could, I don’t know, be a senator here and …” He never did put a bill in, but it’d be a good idea.

TS: Well, that’s something we see, too. You know, we go to our school board, and we negotiate for our contracts. And the school board is stuck. They’re like, we’re not financially getting anything in. We’re paying you what we can, but financially, we’re not getting in what we need. And so, you feel underappreciated by your school board, even though you know, it’s not necessarily their fault. You just feel so underappreciated for what you do every day. I mean, we love our kids. We show up, we make sure our kids are fed, we make sure they’re clothed. If there’s an issue, we have to report it. You know one kid didn’t sleep last night, so you let him sleep in class. You know, we’re parents to a lot of these kids, and we just feel really underappreciated at the end of the day, all the hours that go into it, in the classroom and outside the classroom. This is not an 8 to 5. You go home and you think about your kids all night. You fall asleep thinking about them. You wake up thinking about them.

It’s said that it takes a village to raise children. Especially in our smaller rural schools, it seems the entire community is keeping an eye on students and making sure that you’re staying on track with your education, and they’re celebrating your successes. Have you felt that growing up in Flasher?

SJ: Oh, yeah. Everybody’s always watching, so everybody knows what everybody’s doing. But, I mean, when you qualify for nationals, and you go knock on doors, asking, do you want to buy a bracelet or whatever? I mean, they’re always the first people to say yes. I know the kids that are going to nationals, they put on a supper at the bar, and they bussed tables, and people showed up all night long.

TS: They held the same fundraiser a couple of years ago for the basketball team, and people flocked in for that. At the beginning, I thought, okay, it’s education, let’s see who shows up. And we didn’t have a great turnout of people, but the financial gain we made from that, the people that did show up, it was incredible. Because they wanted to support education instead of athletics.

As a student, do you find that when you’re invested in a subject, and really passionate about it, you’ll get better results?

SJ: Yeah. I think the more passionate you can become about something, the more doors it opens. Last year, I got a $40,000 scholarship from Jamestown through science fair. I think the more you care, the more doors that open, the more people you meet, the more experiences you get.

You mentioned that you got third place at regionals for this year’s project on teachers. How did you fare at state competition?

SJ: That was at regionals. Yeah. At state, I didn’t get anything.

TS: So, I was shocked! For the record, I think she got sixth, so she was, like, one under ISEF qualifying. One under!

SJ: Next year.

TS: Next year! Next year.

SJ: It makes you want it more. … And then, at regionals, I got the National Geographic certificate and American Psychology.

This week is Teacher Appreciation Week so I would like to get just your thoughts on your appreciation for Mrs. Schafer or any of the teachers who have have been there for you as you’re growing up and have sparked that curiosity and passion for learning.

SJ: I would say that all the teachers that have been my biggest mentors are all extremely well-rounded in a lot of different aspects. Obviously, Mrs. Schafer being one of them. And then they all, they all care enough to, you know, they catch me slacking with my research, she’s going to say, ‘You’d better go fix it.’ So I think it’s just their ability to continue to push us, even though they’re so exhausted themselves, that they still care enough to show up every day and help us and answer all my questions.

What are some ways that a student can show their appreciation for a teacher who went the extra mile for them? Something like sending a card or calling them up and sharing their thanks?

SJ: Yeah, I don’t know if a card would get more teachers to come into the system. But I wish we could do that! I’d be writing cards all day! But I think just, I think if Mrs. Schafer got a card from alumni now, I’m sure she’d probably appreciate it.

TS: I do! It’s getting a phone call from a kid or seeing a kid, and having a kid say thank you for teaching me that, because I needed that later. That’s the big one. Or I have kids calling, going, “I don’t know how to do this! Can you help?” They’re in college, and they have their college professors, and instead they turn back to me and ask, can you help me do this? I think those are the biggest payoffs, those kids appreciating you later in life, and telling you, “Thank you for forcing me to do that, because it paid off in the long run.”

NA: There’s this guy who is a friend of ours, and his name is Ted Dintersmith. He wrote a book and produced a movie called What Schools Could Be. When he was writing that book, we talked quite a lot. But his idea is the same thing, the idea that if you’re teaching kids something that they’re passionate about, they’re going to remember that. You’re going to get the card or the phone call from those kids. But he said, nobody would ever send somebody a note saying, “Hey, thanks for teaching me about quadrilaterals. I use it every day.”

TS: Hey, I did use the quadratic formula!

In closing, Sophia, I’d like to ask if there’s one last message you’d want to share with our audience of members of North Dakota United who are educators and maybe feeling the extra pressures of their profession currently?

SJ: Yes, keep showing up. I mean, somebody cares. You’re making an impact on somebody. Maybe you don’t see it every day, but if you’ve got a class of 20, I’m sure you’re making an impact on at least one kid. One kid looks up to you and cares about you, and you’ve got to give back to them.